👖 4 levers can make-or-break a DTC brand

Launching a DTC brand in a challenging category (women's apparel) has taught me some tough lessons on building a brand that can scale

Hi Friends,

Thank you for tuning in for this week’s edition of Curious Commerce. I’m so happy to have you here! I’m Melina. I work as a strategist for retail and consumer businesses, and have my own womenswear brand, Keaton.

Curious Commerce is my weekly attempt to decode the future of commerce, inspired by other disciplines and my own experiences. With that, let’s dive in to Issue #3!

Last week, I shared a few thoughts on the future of the DTC landscape. The past few years saw a massive unbundling of brands and retailers, facilitated by advancements in e-commerce logistics and cheap digital marketing that allowed brands to sell directly to consumers. Pretty soon, we had a website for toothbrushes (actually many), one for toothpaste, and yet another for floss. No matter how seamless transactions have become, there is friction in having to transact on multiple sites for what used to be a single aisle in a CVS. Coupled with increasing advertising costs, DTC started to lose its luster. A re-bundling is already underway—brands are coming together in various organizational structures to preserve what works about the DTC model while eliminating what doesn’t. I’ll be revisiting these emerging business models in more detail next week.

But where does this leave my nascent brand?

Keaton’s Perfect Pant in action.

I’m the founder of Keaton, a 1-year-old e-commerce brand that developed the Perfect Pant for women. I’m often asked what I’ve learned during my startup journey, and I struggle to provide a coherent response. Potential answers range from “the differences between an LLC and a Corporation” to “how to respond to trolls on social media.” In the age of Zoom calls from the couch, pants have been made temporarily optional and I have a bit more time on my hands. I’ve spent the past few weeks reflecting on what’s next for us, and hope that these insights are useful to other founders and operators.

When I launched my brand, I tried a lot of things that didn’t work. I encouraged customers to share their Keaton outfits online, only to realize that women don’t take photos of themselves at work (a few grainy mirror selfies excepted). I worked with microinfluencers and grew my follower count, but didn’t convert many sales. I did trunk shows at offices and learned that women don’t try on clothes while at work. While customers shared very positive feedback on the product and many repurchased, I couldn’t seem to generate the sales growth I needed to think about a VC-backed future.

I realized that women’s pants are an incredibly difficult category to scale. I had to face the facts. It was every MBA’s worst nightmare.* Keaton is a lifestyle business.

*Because I have subscribers who don’t know me personally (hi, lovely to meet you all!!) I want to clarify that this is sarcasm. There is nothing wrong with a lifestyle business, and I hope to one day grow Keaton into a successful one! But the prevailing perception among many of my MBA peers (and among the tech press, until very recently) has been that the amount of VC money raised is a key indicator of a business’ worth. This is probably because fundraising totals are one of the few publicly available data points for an early-stage, privately-held business. The reality that many successful companies grow slowly over long, LONG periods of time is not as glamorous as the alternative narrative.

From analyzing the landscape, I’ve found that four factors are relevant when thinking about how effectively a DTC business can scale:

4 Scale Factors

Universality: Does one size fit all?

How many product variations are needed to reach your audience? For many consumer goods, brands can launch with one or two SKUs. For apparel, multiple sizes (and potentially size ranges) are required. More variations require a higher level of inventory (and therefore higher capital requirements). More variations also make the product less “contagious” within social networks. A friend recently recommended a bra company to me, but she has a very different body shape. I trust her recommendation, but I don’t really think it applies to me. I will probably not shop there. This is different than if my friend recommended a water bottle.

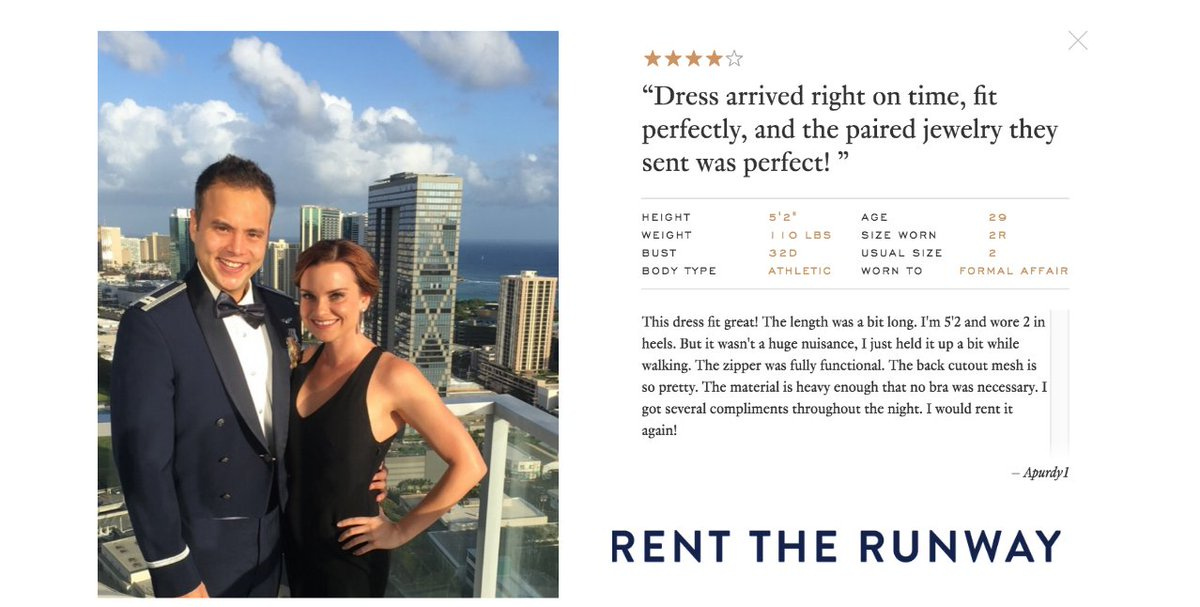

Implications for Keaton: To combat this challenge, I need to invest more in education around fit and sizing so that customers will feel comfortable trying us (and feel that others’ recommendations are relevant to them). Rent the Runway does this very well, by highlighting the body dimensions of those leaving each review. We are relaunching a new version of the site soon that will feature richer review capabilities.

Share-ability: Is it easy to pass the product on to others?

This element was raised to me by a mentor, who liked the recognizable slit detail at the front of The Perfect Pant. There are a few ways this can manifest:

Brandedness

Most obviously, the product can feature a logo that tells others where it’s from. Even without a logo, an aesthetic can be recognizable, like the Allbirds shoe. Allbirds has sued several copycats to protect its signature Wool Runner design. With a noticeably brand product, the customer is sharing it just by wearing it. The signature lining of Bonobos pockets or the silhouette of Untuckit shirts are examples of ways this has translated to apparel.

Structural share-ability

Some products are easier to share structurally. Beauty products are handheld and easy to photograph. They are applied to the face and “looks” can be shared via selfie. Notably, Glossier was the leader in encouraging social sharing in beauty. On the other end of the spectrum, it’s harder for women to take well-lit full-body shots of themselves in clothes (something I learned the hard way after struggling to encourage this behavior among my early customers). Outdoor Voices circumvented this with cute mirrors in their changing rooms.

Talkability

A third dimension of sharing is word-of-mouth. Certain categories and experiences are more novel and prone to sharing than others. Alcohol substitutes are very talkable among my “too old to drink anymore” 30ish friends. I’ve tried both Haus and Kin Euphorics on friends’ recommendations. Harder to talk about? Personal care categories like tampons. Destigmatizing period talk has been an ongoing initiative for brands like LOLA. When I interned with the team during my MBA, I proudly shared my #firstperiodstory on their Instagram, part of a weekly feature series.

Implications for Keaton: I underestimated how difficult it would be to encourage UGC. I’ve recently started to partner with microinfluencers (typically unpaid partnerships in exchange for free product and candid reviews), which yields high-quality but unstaged product imagery. My content strategy revolves around becoming part of the conversation as young professional women build their work wardrobes, providing useful information to help women like me navigate the unwritten rules of corporate office dressing.

Trialability: is it easy to test the product?

The barriers to try a new product should be as low as possible. For categories like beauty, fragrance, food, and beverage, it’s fairly simple to produce and disseminate samples. More abstractly, home try-on programs, which were popularized by brands like Warby Parker and currently used by brands like Harper Wilde (bras) and Aurate (jewelry) allow extended no-risk trial before purchase.

Implications for Keaton: To encourage trial, I prioritized trunk shows early on in my marketing strategy. Many of these took place after work at cocktail events in partnership with other brands. I realized that women were tired after work and didn’t want to undress to try pants on. While touching the product was helpful, I didn’t get a fully-realized trial. Partnerships with local boutiques or a home try-on option could be explored in the future.

Purchase frequency: How often do customers buy?

The ideal quick-to-scale business model is a product that is purchased consistently by each user in accelerating quantities over a long period of time. Subscription models are a good fit for some consumable categories. Apparel and footwear businesses, especially on the fashion side, tend to have lower purchase frequencies.

Implications for Keaton: When I started the business, I viewed the pant as a utility good. This was a key piece of my thesis. My research showed that many women are of two minds when it comes to clothes--we have “uniform” pieces of which we own multiple of the same or similar items (for me, Everlane tees and Lululemon leggings) and “fashion” pieces that are one-of-a-kind in our wardrobe (cocktail dresses, fun tops). For many, workwear falls into the “uniform” category. This has held true in reality--I’ve had customers purchase multiple pairs of the Perfect Pant. My question as we grow is how to balance a workwear uniform with the desire for individuality and style, all within a small number of SKUs.

What’s next

There are many ways to learn from my first year and mitigate some of the challenges that apparel companies like mine face to scaling. Given my level of resources and the dynamics of my category, I believe that switching my focus to being cash flow-funded and growing organically is the best path forward.

It is no coincidence that successful DTC exits like Dollar Shave Club are high on these scale factors. It’s interesting to note that brands like Casper, which have recently struggled, lack many of these scale elements (purchase frequency, brandedness, structural share-ability, and some would argue universality). This framework clearly does not explain everything (unit economics and launch timing are two obvious elements I’ve left out) but it provides a useful tool.

Should I have figured all this out before launching a pants company?

I launched Keaton because I am genuinely obsessed with the challenge of dressing for work as a young professional. The fundamentals of the business are strong. What I’ve learned in my first year is that I need to adjust my expectations for growth and my strategy accordingly.

I’ve always loved fashion. The things that make it a tough category in which to scale a business--its individualism, it’s dynamism--are what make me love it. I look forward to what I’ll learn in Keaton’s second year!

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to subscribe for weekly reflections on the future of consumer and retail!

What I’m Reading

📚 The Overstory - Richard Powers. I’m leaving this one on here for a second week because I’m still thinking about it. *Support your local indie and shop with my Bookshop links*

📰 The Pandemic Will Change American Retail Forever - Derek Thompson. He predicts that in cities, a period of closures will precede a revitalization as cheaper rents and costs of living attract a more diverse population of businesses and consumers.

📰 How the Virus Transformed the Way Americans Spend Their Money - New York Times. Nice visualization of spending by category. Everything except groceries is down. I found this in Sarah Shapiro’s fantastic weekly retail newsletter.

Stay Curious,

Melina