Hi Friends,

Thank you for tuning in for this week’s edition of Curious Commerce. I’m so happy to have you here! I’m Melina. I work as a strategist for retail and consumer businesses, and have my own womenswear brand, Keaton.

Curious Commerce is my weekly attempt to decode the future of commerce, inspired by my background as a consumer brand strategist and startup founder. If you enjoy this article, be sure to subscribe for weekly reflections on the industry!

These past few weeks, I’ve been torn between feeling discomfort with all of the uncertainty in our lives and feeling excitement to be working and building in the consumer space during such a dynamic time. Most days, it’s a mix of both. It feels like we’re in the midst of a dramatic reshaping of the consumer landscape, with outcomes that will last for many years.

While the former management consultant in me is itching to fit everything inside a neat, unifying framework, I think there is value in taking some time to outline what the heck has happened over the past couple of weeks.

Major players from Facebook to Amazon announced new initiatives that put them in greater competition with one another and with the traditional world of department store and multi-brand retail. A new algorithmic-discovery engine for shopping launched, called The Yes. And Shopify has been VERY busy.

Shopify

Shopify is having a wild few weeks. They launched their Shop app and hosted their Reunite broadcast for business owners. During this session, they indicated their intention to challenge long-time players in the Shopify ecosystem by offering services like installment payments, messaging, and email. This directly threatens the business model Afterpay, Klarna, and others. They also highlighted partnerships with Google Shopping and Facebook Shops.

Shopify has always positioned itself as a platform to enable the success of its brands, and the effect of these announcements cements this brands-first focus:

Collapsing the “eCommerce stack”

By offering installments, messaging, and Shopify email (which will be free to users through October), Shopify is reducing the need for brands to contract with third-party services. The cost of building the “eCommerce stack” for your brand on Shopify can quickly add up. For my brand, I use Klaviyo (email) and two Shopify apps that charge a monthly fee in exchange for custom theme features. This in addition to the monthly fee charged by the Shopify platform. Reducing the number of external integrations that brands must pay for increases “stickiness” to the Shopify platform and also increases profitability, which over the long term results in greater usage of the platform. For new brands, it makes it easier to get up and running.

It appears that Shopify’s strategy is to go through the checklist of how to start a new business on the platform and build a service offering for each step. They already offer free logo design services, and last year released Shopify Capital to provide quick financing for small businesses. I wouldn’t be surprised to see them venture into services like trademarking automation and company formation, which are significant barriers to entry for small business owners.

Shop unlocks a new customer touchpoint

When Shop launched, many speculated that Shopify was moving to create a marketplace that would recommend new brands and products in a way similar to Amazon. However, after seeing the Shop roll out and the announcements at Reunite, I’ve come to hold a different view.

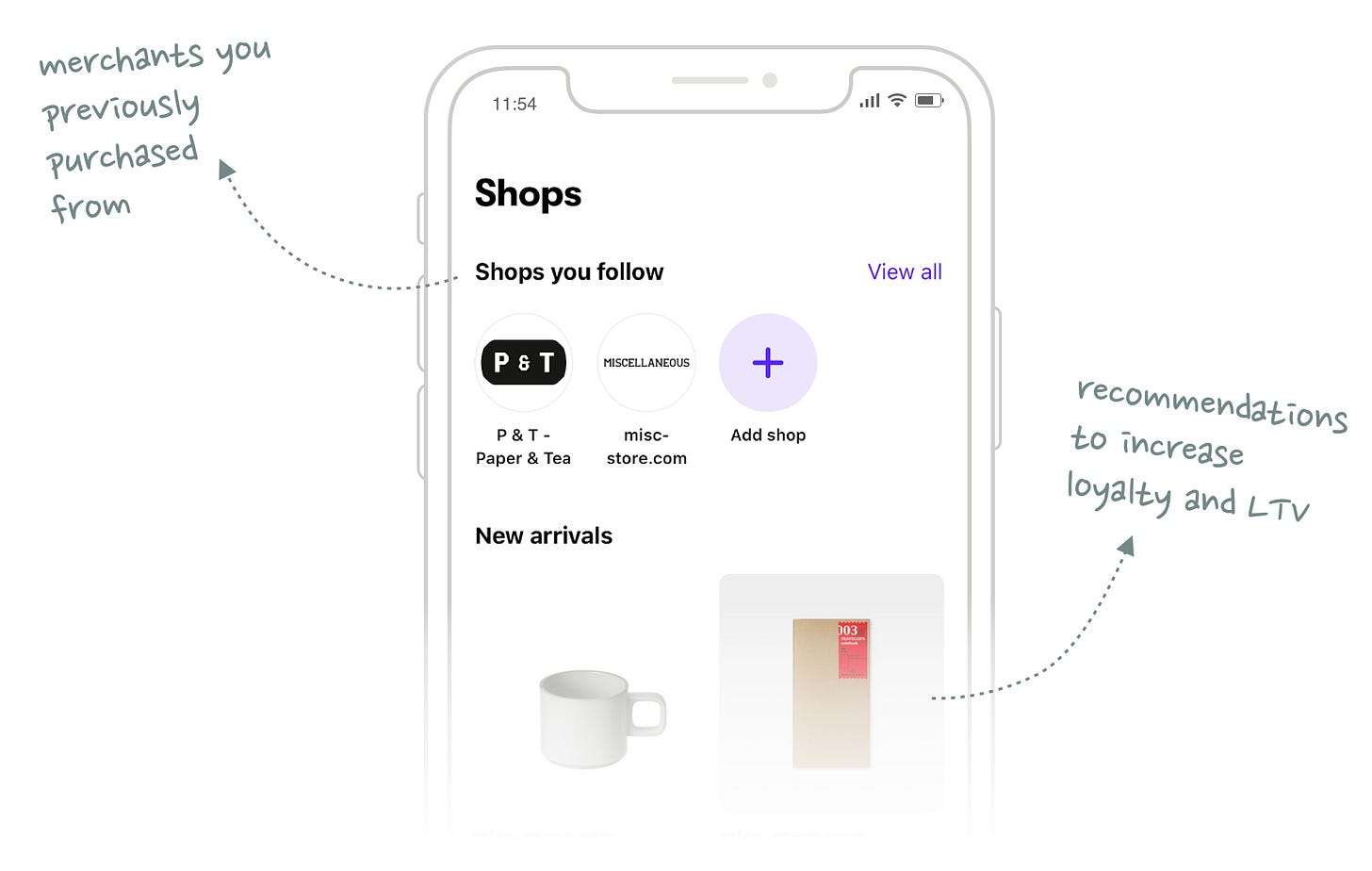

As this outstanding piece by Julian Lehr argues, the Shop app isn’t really about discovering new brands. Instead, the app shows you brands you’ve already bought from (and discovered independently). It then highlights additional products to build the customer relationship and increase LTV.

Image source

Why this approach?

From the Julian Lehr piece:

Many of Shopify’s merchants aren’t really direct-to-consumer brands, they are more like direct-to-consumer-but-with-Instagram-in-the-middle-eating-all-of-their-margin brands. Instagram capturing most of the value is a perfect example of why demand aggregation is always more powerful than supply aggregation. Too much reliance on a powerful gatekeeper like Instagram is a risk for Shopify and its merchants.

Shopify wants to unlock a new channel for brands to reach customers that isn’t Instagram (or Pinterest or Google). So long as brands are forced to rely on these channels to acquire customers, much of Shopify’s success (as measured by the success of the brands on its platform) is out of its hands. The Shop app was born from a place of utility—tracking orders and delivering order notifications—but it has moved beyond that to enable brands to communicate with customers. Shopify announced at its Reunite conference last week:

Soon, merchants will be able to use Shop to tell their brand story, by customizing how and where their brand shows up in the app.

In other words, they are working to evolve the app to become a channel for storytelling and upsell/cross-sell that will free up margin for their partners and cut out marketing middlemen. Whether this will cross into customer acquisition/discovery remains to be seen.

Facebook

Facebook launched Shops, enabling businesses to set up free storefronts on Facebook and Instagram. The rationale, via Techcrunch:

the pandemic has probably made consumers even more likely to treat Facebook and Instagram profiles as the go-to source of information on local restaurants and stores — if your favorite store has changed their hours, or switched to online delivery/curbside pickup, they’ve almost certainly posted about it on Facebook or Instagram. So why not allow visitors to make purchases without having to leave the Facebook and Instagram apps?

This will be really interesting launch to watch. Facebook has had years to see what is working for brands organically on its platforms. They can take these behaviors and build a new way of shopping that doesn’t feel like shopping.

Amazon

Amazon partnered with the CFDA to sell luxury designer products on the platform. These designers are among the hardest-hit in retail by the crisis, as department store and boutique closures have resulted in canceled orders and excess inventory.

The New York Times neatly summarized Amazon’s track record of attempting to break into fashion:

In 2011, the company introduced myhabit.com, a flash sale site meant to compete with sites like Gilt Groupe. That closed in 2016, the year after Amazon teamed up with the CFDA to sponsor the first New York Men’s Fashion Week (a relationship that ended in 2017). That same year Amazon Fashion went all-in with private label clothing, a category that now includes 111 different labels and 22,617 products, according to a new report from Coresight Research.

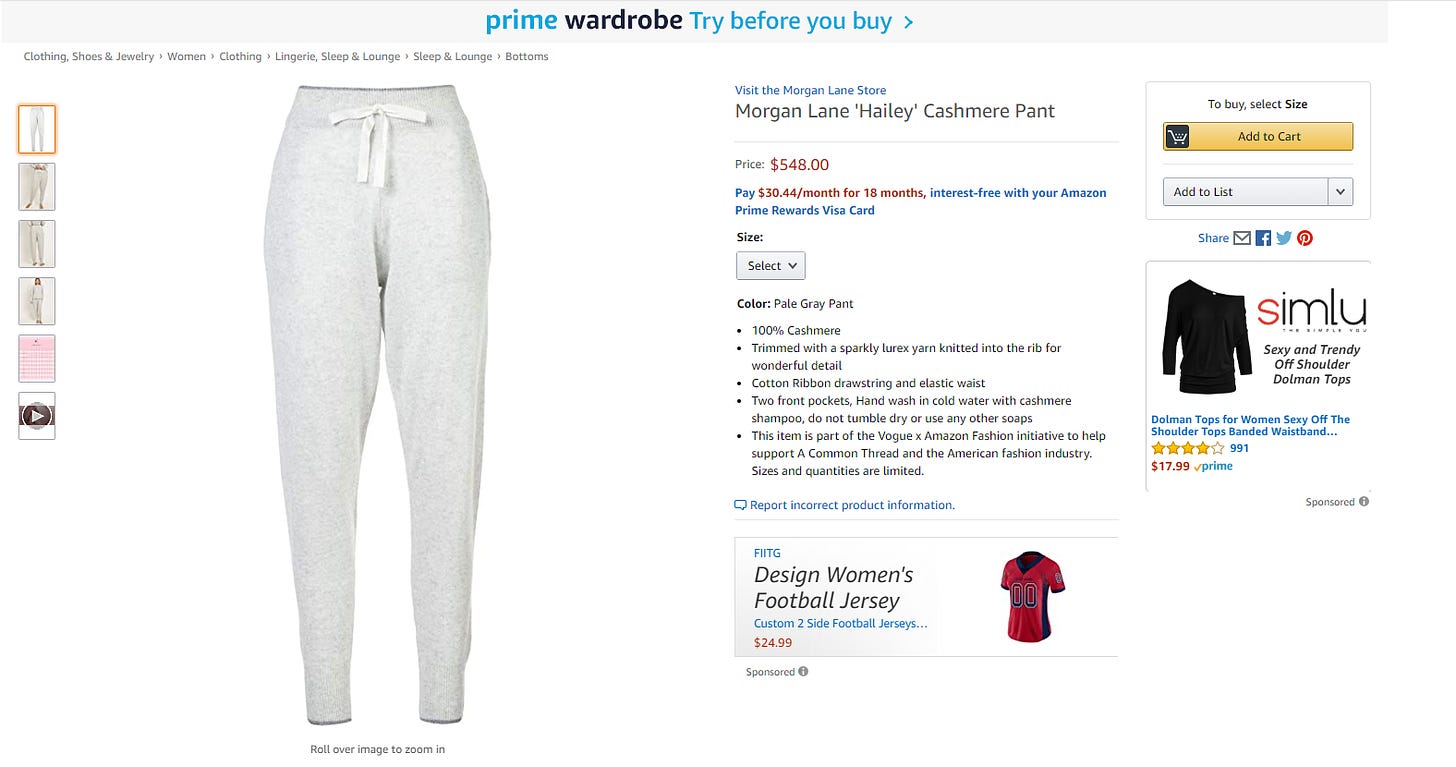

This latest move strikes me as a bit odd. There is much to be desired in terms of implementation and branding. The product page below advertises a $548 pair of cashmere lounge pants, yet the ad units on my page link to items costing $17.99 and $24.99. Not a good look!

In a physical store, a customer would sip champagne while a stylist selected these pants for her to try, along with other items that fit her style and needs. As an indebted recent MBA grad, I’m not often shopping at luxury boutiques, but I can imagine that the experience makes customers feel special and catered to in a way that browsing Amazon does not.

It’s unclear how luxury brands will remain competitive if they are forced to rely on channels that can’t adequately communicate a brand’s story and unique value.

The Yes

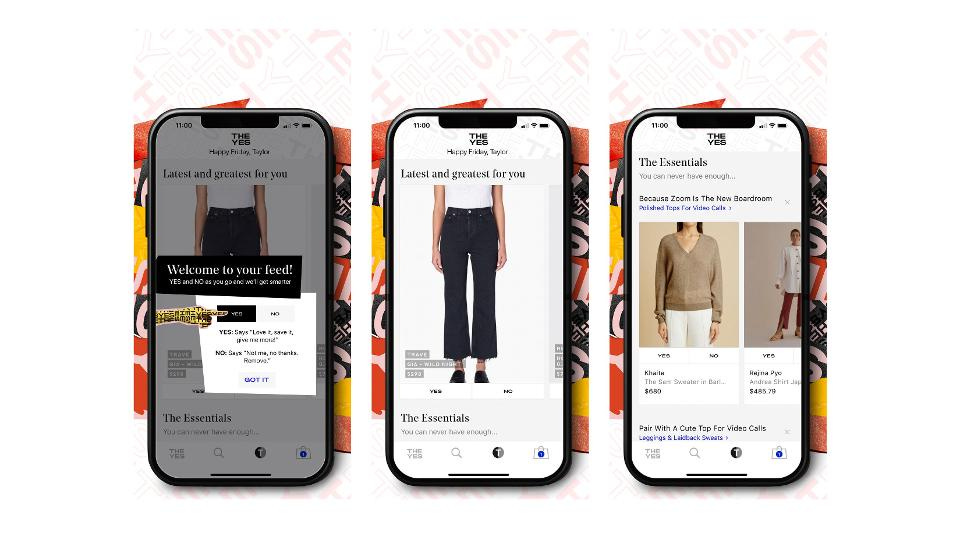

Last week, The Yes, an algorithm-driven shopping app founded by former Stitch Fix COO Julie Bornstein launched. I’ve been playing around on the app (the service is app-only) all weekend and think it’s super interesting.

A few things stood out:

High-low shopping: There is a significant range of price points in the assortment, which is both a strength and potential challenge. I agree with Bornstein’s assertion that women tend to shop “high-low.” We are apt to pair a $50 pair of Outdoor Voices bike shorts with $500 sneakers. This has become especially true in recent years. It is a bit jarring to see a $20 tee next to an $800 dress in the app. I wonder how they will curate these collections to make this flow more naturally.

Taxonomy of fashion scaled through machine learning: I wrote in a previous post about how it was harder-than-expected to scale my brand (a fashion product) because of the nuanced and individual nature of fashion choices compared to other consumer categories. All white tees are not created equal—fabric weight, silhouette, neckline, sleeve, and other less articulable details all influence whether I’ll want to wear something. The Yes’s fashion algorithm includes 500 attributes for each product, which can be integrated with user inputs to personalize a feed of products and brands. So far, my results are pretty in-line with my actual style, which is pretty impressive. This data is very valuable, as it can be used to help brands design more marketable items or as an input into private label collections.

Lightweight solution: The Yes leverages brands’ existing creative assets and doesn’t hold inventory. It simply provides the matching engine between customers and products.

A service like this, which enables discovery of new brands and highlights relevant products for each customer, has the potential to replace what the department store has traditionally offered. Further, these solutions offer a channel for higher-end brands to reach new customers via eCommerce in a way that is more brand-right than Amazon.

So What?

My internal former management consultant is “circling back” again to ask “so what?” All these stories are about companies doing cool things. But what do these development signal for the future of commerce? I don’t have a full answer just yet, but there are a few commonalities that emerged from all of these announcements:

Global meets local

I wrote in a previous post about how shopping with local businesses will be a status symbol during these times. I predicted:

New services that enable consumers to discover and support small businesses will boom.

It’s interesting to see how all of these announcements—even from global behemoths like Facebook and Amazon—have been couched in terms of “support for small businesses.” Amazon’s partnership with the CFDA is in support of A Common Thread fund, which supports local designers. In the livestream announcing Facebook Shops, Mark Zuckerberg said, “We’re seeing a lot of small businesses that never had online businesses get online for the first time.” It’s fantastic that small businesses can access these services, but global marketplaces are the ones truly pulling the strings.

Curation is everything

The balance has shifted from offering customers more choice to presenting fewer, more relevant choices. The launch of The Yes exemplifies the shift. The Shop app from Shopify also curates a personalized assortment by showing customers products from brands they’ve interacted with before. Even Amazon’s CFDA partnership represents a limited assortment of brands in a Collection format.

Death of department stores?

Facebook, Amazon, Shopify, and The Yes are creating these offerings because brands are eager to get on board. If brands were reaching customers cheaply and effectively via the department store and multi-brand retailer model, they wouldn’t be so willing to give these other services a go. As these players get better at enabling product discovery and brand storytelling online, it will be harder for department stores to maintain an advantage.

I look forward to seeing what’s next and reporting on these services and platforms as they continue to evolve.

If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter so far, please consider sharing with a friend or two:

✨ Stay Curious,